Catholic convert uses every means possible to share Chesterton’s work

Part two in a 14-part series highlighting local Catholics who live out the corporal and spiritual works of mercy

George Preca of Malta. The rosary’s luminous mysteries. The Lord’s Prayer, the Greek word for “debt,” and the interchange of “justice” and “righteousness.” Standing before 18 high school sophomores in early December, Dale Ahlquist tied each topic into a 45-minute lecture on Christ’s Sermon on the Mount and the Beatitudes.

Also mentioned was G.K. Chesterton, the early 20th century British writer who turned Ahlquist’s life upside down — or right-side up, depending on the perspective.

Pointing to Christ’s commandments such as “love your enemies” and “blessed are the poor,” Ahlquist, 57, explained to the students that “the whole Sermon on the Mount — Matthew 5, 6 and 7 — is absolutely jam-packed full of paradoxes.”

“It’s almost as if Chesterton had written them,” he added, nodding to an ongoing theme Chesterton Academy students are expected to understand.

“Paradox is truth standing on her head to attract attention,” Chesterton wrote in one of his detective stories, and it’s a concept at the heart of his writing, as well as central to the writer’s argument for Christianity. He dedicates a chapter in his 1908 book “Orthodoxy” to Christianity’s paradoxes, the foremost being that Christ is fully God and fully man.

“Orthodoxy” is read by all freshman students at Chesterton Academy, a high school Ahlquist, a parishioner of Holy Family in St. Louis Park and father of six, helped found in 2008.

The high school was a milestone in a series of Chesterton-motivated endeavors Ahlquist and his wife, Laura, have undertaken in the years following his discovery of Chesterton while on their honeymoon. Others include seven seasons of a show dedicated to Chesterton on the Eternal Word Television Network (EWTN), numerous lectures, several books, the founding of The American Chesterton Society and a national conference.

At the core of the work is Ahlquist’s insatiable passion for the wide-ranging thinker and his desire to see him better read and understood, and maybe one day even declared a saint. As Chesterton taught him, Ahlquist has made it his life’s work to teach others, fulfilling a spiritual work of mercy: instructing the ignorant.

‘I couldn’t get enough’

Ahlquist was raised a devout Baptist in Mendota Heights. While an undergraduate at Carleton College in Northfield, he met Laura, then a fallen-away Catholic. The two married in 1981 and honeymooned in Rome, where Ahlquist dove into Chesterton’s 1925 tome “The Everlasting Man” because it was the work responsible for converting C.S. Lewis from atheism to Christianity.

“As soon as I started reading Chesterton, I knew this was a writer unlike any other I’d ever encountered. He was a truly complete thinker because he wrote about everything and he pulled it all together. Great wit, great insight. The truth just oozed from his words,” he said. “I just totally fell in love with him. I couldn’t get enough Chesterton.”

Gilbert Keith Chesterton (1874-1936) was born in London, went to art school — not college — and started his writing career in art criticism. In his lifetime, according to The American Chesterton Society, he wrote 100 books and contributed to 200 others, more than 200 short stories, hundreds of poems, five plays and more than 4,000 newspaper essays.

His magnitude was not limited to writing; he was 6 feet 4 inches tall and 300 pounds. He was an absent-minded man whose wife took care of his life’s details, who appreciated beer and cigars, and who debated his era’s top minds, among them Bertrand Russell, H.G. Wells and George Bernard Shaw — the latter of whom is said to have remarked, “The world is not thankful enough for Chesterton.”

Despite Chesterton’s prominence during his time, Ahlquist discovered in the early 1980s that most of the author’s books were out of print. He dug through used book stores for Chesterton’s works, baffled as to why the whole world wasn’t reading him. He tried to overlook the fact that Chesterton was a Catholic convert, he said — “How could someone who was so right about everything be so wrong about something so fundamental?” he mused.

His conversion to Catholicism was underway.

“What was happening while I was reading Chesterton was that my Protestant objections were just falling by the wayside. I was becoming Catholic without even being aware of it,” he said. “Finally, I had to acknowledge that . . . I was very much in danger of becoming Catholic.”

Hungry for the truth

He began to study Catholicism, and in 1997, Ahlquist was received into the Catholic Church at the Cathedral of St. Paul in St. Paul by now Bishop Andrew Cozzens.

Meanwhile, Ahlquist was starting The American Chesterton Society, for which he later left his work as a lobbyist to run full time.

“The idea behind starting The American Chesterton Society was simply, more people need to find out about this guy,” he said. “This is ridiculous. Why has a whole generation been cheated out of such an amazing, wise and profound writer? He transformed my life, and here was a writer who could transform other people’s lives. My goal was to expose as many people to Chesterton in as many ways possible.”

His work caught the attention of Marcus Grodi, host of EWTN’s show on Catholic converts, “The Journey Home,” who invited him to speak about Chesterton on the show. After filming his segment, a producer asked Ahlquist if he would consider hosting a series on Chesterton. In 2000, he launched “The Apostle of Common Sense,” which aired 100 episodes and has played a significant role in a Chesterton renaissance.

Today there are about 70 local Chesterton Societies across the country and world, Ahlquist is a sought-after speaker for small audiences to Ivy League lecture halls, and The American Chesterton Society hosts annual conferences across the U.S. It also launched a bi-monthly Chesterton-focused magazine, Gilbert.

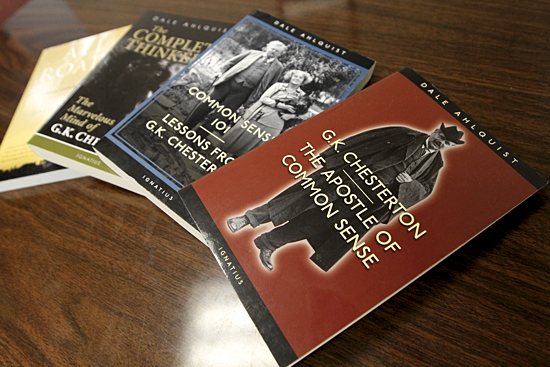

The society has worked to re-publish Chesterton’s works, many through Ignatius Press in San Francisco, and has its own publishing arm, ACS Books, a TAN books imprint. Ahlquist has also written four books on Chesterton, introductions for 25 others and has edited eight more. His current work includes combing through old British newspaper archives for reports of Chesterton’s public speeches. It’s been exciting to discover new material, he said.

“I am sometimes asked if I read anything besides G.K. Chesterton,” Ahlquist wrote in the introduction to his 2012 book “The Complete Thinker: The Marvelous Mind of G.K. Chesterton.” “The answer, unfortunately, is yes. I wish I had a better answer — something along the lines of no. It would save me a lot of time and frustration if I did not have to read other authors.”

Ahlquist calls Chesterton “truly a prophet.”

“If he’s right, it’s still worth reading him,” he said. “He foresaw the attack on the family, the loss of human dignity because of disparity in wealth, widespread wage slavery . . . . He says the whole modern characteristic is slavery, whether it’s physical slavery or mental or spiritual slavery. The Church is all about freedom and liberating people.”

The premise of Ahlquist’s most recent book, “All Roads” (ACS Books, 2015), is that every conversation is an opportunity to be an apologist for the Catholic faith.

“When I do tell people about the truths of the faith, their reaction is, many times, they soak it up,” he said. “They are hungry for the truth. They have a very positive response.

But you also have the negative response, and what Chesterton enjoyed so much was controversy.”

A treasure to share

Asked what he made of “instructing the ignorant,” Ahlquist compared the spiritual work of mercy to the corporal work of mercy of feeding the hungry.

“If you give food to the hungry, the people know they’re hungry. The people who are ignorant don’t always know they are ignorant,” he said. “But when you give food to the hungry, you don’t do that arrogantly, you do that humbly, because you realize that person is suffering, so you’re suffering with them by feeding them. I realize that in defending the Catholic Church and in teaching the Catholic faith, it can only be done humbly. I’ve found a treasure, and I want to share this treasure.”

Laura Ahlquist counts herself among the ignorant for whom Dale revealed the truth.

“I was so badly catechized that the faith didn’t make any sense to me at all. When I met Dale, he was this on-fire Evangelical, and he actually taught me that the faith was rational,” she said. “He, in a way, brought me back to Christianity.”

Laura, 55, returned to Catholicism when Dale and their two oldest children joined the Church. She now is administrative dean of Chesterton Academy where she also teaches drama.

Ahlquist “has a way of winning people over,” because of his zest and humor, said Ben Wittnebel, 30, a third-year seminarian at the St. Paul Seminary who has appeared on “The Apostle of Common Sense.” “It disarms you, and then you catch the spirit of his passion.”

Wittnebel discovered Chesterton by watching “The Apostle of Common Sense,” and the writer — especially his biography of St. Francis of Assisi — played a major role in his conversion from the Lutheran tradition to Catholicism in 2006. “There’s something about Chesterton, where his whole charism is wonder — wonder and gratitude, and Dale inspires that in people,” he said.

By reintroducing Chesterton to the world, he said, “Dale has actually done this really great service to the Church.”

Ahlquist keeps a list of people — Wittnebel included — who have converted to Catholicism because of Chesterton. It has more than 400 names. People call him to share their stories, relay the impact of Ahlquist’s work and ask questions about the Catholic faith. According to Laura, these conversations take hours of Dale’s time.

Ahlquist thinks their stories may help make the case for Chesterton’s sainthood. In 2013, with the prodding of The American Chesterton Society, the Diocese of Northampton, England, appointed a priest to investigate opening a cause for Chesterton’s canonization. In Ahlquist’s mind, there’s no question that the status is appropriate.

“With Chesterton, what happens is that you really do develop a friendship with him. That’s what the communion of saints is all about,” he said. “I have no doubt he is in the presence of God. His righteousness, his goodness come out in his writing, and there’s a connection between truth and goodness.”

Leaving the boat

Since 2008, Ahlquist has taken his love of Chesterton to the classroom. Ahlquist partnered with fellow Holy Family parishioner Tom Bengtson to co-found Chesterton Academy, now located in Edina in space rented from a Calvinist church.

The high school was a leap of faith, and another reason Laura describes what Ahlquist does as a vocation, not a career. It’s since formed the Chesterton Schools Network with nine other U.S. schools — and another in Italy — using its curriculum, and Ahlquist plans to open Chesterton campuses in the Twin Cities’ east and south metro areas in the next few years.

Ahlquist’s friend and collaborator on “The Apostle of Common Sense” Kevin O’Brien said Ahlquist once described his endeavors as setting his eyes on Jesus, trustingly stepping out of the boat and on to the water, and walking without stopping.

“His ability to trust divine providence is what sticks out to me,” said O’Brien, 55, for whom Chesterton was key for his conversion from atheism to Catholicism. He’s the founder of and artistic director for St. Louis-based Theater of the Word Incorporated, which has dramatized scenes for Ahlquist’s show.

“It’s not just what he says, but who he is, because I think we really teach more by example and by who we are as people than by the things we say,” he said. “Dale’s very good at teaching and lecturing and writing, but I think you’ll find both at Chesterton Academy and in The American Chesterton Society, that it’s his character, it’s his outlook on life, it’s who he is as a person that really inspires the people who are learning from him.”

It’s been suggested to Ahlquist before that all this attention on Chesterton could overshadow the person of Christ. He says that’s not possible.

“My epiphany was to realize when I understood the communion of saints was that the saints don’t get between you and Christ, they bring you closer to Christ,” he said.

“Chesterton is always pointing to something beyond himself. He’s always directing you to God.”