Complicated legacy includes handling of sexual abuse allegations

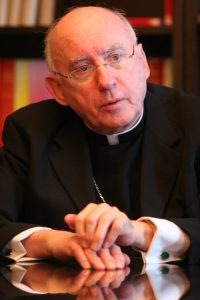

In the 13 years he led the Archdiocese of St. Paul and Minneapolis, Archbishop Harry J. Flynn made time for two things: prayer and people. During his ministry, he was well loved by many for his gentle, personal nature and lauded for his roles in fighting racism, bolstering interfaith relationships and fostering vocations to the priesthood.

The archbishop emeritus of St. Paul and Minneapolis died Sept. 22 at age 86 in his residence at the St. Vincent de Paul rectory in St. Paul. He had battled cancer in recent years.

An all-night prayer vigil and public visitation were set for Sept. 29 at The St. Paul Seminary chapel, followed by public visitation and a funeral Mass Sept. 30 at the Cathedral of St. Paul. After the Mass, the Rite of Committal and burial will be at Resurrection Cemetery in Mendota Heights.

Ordained a priest of the Diocese of Albany, New York, Archbishop Flynn served parishes in his home diocese; was rector of Mount St. Mary’s Seminary in Emmitsburg, Maryland; was bishop of the Diocese of Lafayette in Louisiana and then Archbishop of St. Paul and Minneapolis.

Funeral arrangementsSept. 29, St. Mary Chapel, The St. Paul Seminary

- 5:30 p.m., Reception of the body

- 6:30 p.m. – 7:00 a.m. (Monday) Reception of the Body and Public Visitation

- 7 p.m., Evening Prayer (please note updated time)

Sept. 30, St. Mary Chapel

- 7 a.m., Morning Prayer

- 7:30 a.m., Transfer of the body to Cathedral of St. Paul

- 8-11 a.m., Public visitation

- 11 a.m., Mass of Christian Burial

Orphaned at age 12

Harry Joseph Flynn was born May 2, 1933, in Schenectady, New York, to William and Margaret Mahoney Flynn.

His father died when he was 6 years old.

In September of 1945, with older brothers away in military service, 12-year-old Harry was living alone with his widowed mother. When he woke the day after Labor Day to begin his first day of seventh grade at St. Columba School in Schenectady, he found his mother dead.

He was then raised by a pair of maiden aunts, and he often spoke fondly of two Sisters of St. Joseph — Sister William Edmund and Mother Maris Stella — whom he said shepherded him with tender care through the remainder of his elementary and secondary schooling, which led to his fond regard for women religious throughout his life.

He earned both a bachelor of arts and a master’s degree in English from Siena College, a small Franciscan school in nearby Loudonville, New York.

“Two or three classmates were joining the Franciscans at the time I was thinking about the priesthood,” he said in a 1994 interview. “They said, ‘Come with us,’ but I decided I wanted to stay close to home, and I chose diocesan priesthood.”

He studied at Mount St. Mary’s Seminary in Emmitsburg, Maryland, where he befriended Oklahoma seminarian Stanley Rother, who would later be martyred in Guatemala and then beatified in 2017. The two were good friends until Father Rother’s death, and Archbishop Flynn often spoke and wrote about him. In a 2017 interview with The Catholic Spirit, he spoke of the priest’s attackers: “They killed a man, but they created a saint.”

Archbishop Flynn was ordained a priest of the Diocese of Albany May 28, 1960. As a young priest, he served pastoral assignments and taught at Central Catholic High School in Troy, New York. After five years, however, he was back in Emmitsburg, appointed dean of Mount St. Mary’s Seminary. He served next as the seminary’s vice rector and then rector from 1970-79.

He recalled being at a crossroads in his life in 1979. He was at the point where he felt he had to decide whether he was going to make a life of seminary administration or other ministry. He chose to go back to his home diocese, returning as Albany’s diocesan director of clergy continuing education. Two years later he was named pastor of St. Ambrose parish in Latham, New York, north of Albany. His time in Latham he termed “five gloriously happy years as pastor.”

“There’s something about being pastor,” Archbishop Flynn told the Catholic Bulletin, predecessor of The Catholic Spirit. “One has the possibility of assisting and forming a community and can experience the direction that a community is taking. You’re with people in pain and sorrow and joy. You become one with them. The most comfortable I’ve ever felt was in my years as pastor.”

Those years, however, were to be few.

The Church calls

In 1986, Pope John Paul II appointed him coadjutor bishop of the Diocese of Lafayette, in south-central Louisiana. Then-Father Flynn didn’t want the job. Happy to be a parish priest, he went to his family’s cabin in the Adirondacks to attempt to dodge the appointment.

Hiding was not possible. Cardinal John O’Connor of New York sent a state trooper to bring him back.

As Archbishop Flynn would tell the story years later, Cardinal O’Connor reminded him that it was the Church that was calling him to serve, and when the Church calls, you say yes.

Lafayette was a diocese in crisis at the time, reeling from one of the first cases of priestly sexual abuse to receive national attention. While Bishop Flynn was hailed at the time for his willingness to listen to victims of abuse and his compassionate style in the diocese, victim-survivors and their family members interviewed in a 2014 Minnesota Public Radio investigation said then-Bishop Flynn never reached out. It also reported that he allowed at least one accused priest to remain in ministry and sought to cover up allegations. Archbishop Flynn never publicly addressed the criticism.

When Bishop Gerald Frey retired in 1989, Bishop Flynn became Bishop of Lafayette. He took a strong stance against racism and capital punishment, visited jails and prisons, made a point to visit every Catholic school in the diocese every year. He led days of recollection for all sorts of groups. He also began to personally encourage young men discerning a vocation by inviting them to dine with him and talk about their dreams, an approach he used in Minnesota as well.

It was in Lafayette that he said he first worked with and came to appreciate a collegial style of leadership and what he called “the welcoming love” of not only Cajun Catholics but also a large African-American community. Notre Dame Sister Joanna Valoni, then Lafayette’s chancellor, who spoke with The Catholic Spirit before her death in 2002, said person-to-person relationships were very important to him.

Although the bishop was from the East Coast, she said, “he was able to blend in and be one of us. He also accepts all kinds of people in all schools of thought. He sees the person; he doesn’t see the philosophy.”

It was witnessing Bishop Flynn in action that prompted Archbishop John Roach to place him high on a list of five possible candidates to succeed him as archbishop of St. Paul and Minneapolis when he requested a coadjutor archbishop.

Archbishop Roach and Bishop Flynn both served on the Administrative Board of the National Conference of Catholic Bishops, the leadership body that guides policies of the Church in the United States. Both were also members of the U.S. bishops’ first Ad Hoc Committee on Sexual Abuse by Priests.

In explaining his admiration for Bishop Flynn in a 1994 interview, Archbishop Roach said, “I have seen him operate with the greatest skill, and I know the respect that others have for him. I saw in him some real wisdom and a genuine sense of the sacred character of other people. I saw a tremendous sense of justice.”

Archbishop Flynn later became chairman of the bishops’ Ad Hoc Committee on Sexual Abuse by Priests, and guided it through the challenging days of 2002-2003 as the bishops faced a nationwide scandal, culminating in what would come to be called the Dallas Charter, after the site of the U.S. bishops’ meeting where the charter was approved.

However, in 2013 Minnesota’s statute of limitations on child sex abuse was temporarily lifted, ultimately resulting in accusations from about 450 victim-survivors, including people alleging abuse during Archbishop Flynn’s tenure. Investigations into the abuse prompted questions about some of the decisions he made. When questioned under oath in May 2014, he said he did not remember how he handled sexual abuse cases while leading the archdiocese.

At home in Minnesota

As the seventh archbishop of St. Paul and Minneapolis, succeeding Archbishop Roach on Sept. 8, 1995, Archbishop Flynn executed his office as much as a pastor as an administrator. He said his top priority was “to make the name of Jesus known and loved.”

“Archbishop Flynn had an incredible pastoral gift,” recalled retired Father Bob Hart, noting that history will remember him as “kind, compassionate.”

Father Charles Lachowitzer, vicar general and moderator of the curia of the archdiocese, noted, “Long before Pope Francis coined the phrase, ‘Joy of the Gospel,’ Archbishop Flynn lived that joy and wanted everyone else to share it, too.”

Thanks to the attraction of his joy and his personal enthusiasm for the priesthood, during most of Archbishop Flynn’s tenure the archdiocese ordained more priests than it lost through death and retirement.

Archbishop Flynn “was a ‘pastor’s pastor,’” Father Lachowitzer said. “The first time the new archbishop called me at the parish to simply ask how I was doing and express his gratitude for my priestly service, I thought I was special. It wasn’t too long after my surprise phone call from the archbishop that I found out he had called several pastors with the same message.”

As archbishop he adopted reform for Church employment practices and continued his firm stance against racial prejudice, writing “In God’s Image: Pastoral Letter on Racism” in 2003.

“We cannot be a Church that is true to the demands of the Gospel if we do not act justly, if we do not act to root out racism in the structures of our society and our Church,” he wrote. “And we cannot achieve personal holiness if we do not love tenderly, if we do not love and respect all human beings, regardless of their race, language or ethnic heritage.”

During his tenure, he greatly expanded the availability of the Mass in Spanish, launched an evangelization initiative in 2004, and worked to advance the Catholic Church’s relationships with local Protestant, Jewish and Muslim communities.

He also approved the name change of the diocesan newspaper from the Catholic Bulletin to The Catholic Spirit. The archbishop wrote a column for each issue, praised the newspaper staff for the ideological balance the publication presented, and, as publisher, often mentioned The Catholic Spirit in his speaking engagements as a way to encourage readership.

He retired to archbishop emeritus status May 2, 2008, after serving as archbishop in the Twin Cities and surrounding counties for 13 years, but he continued to assist in the archdiocese with confirmations and liturgies. In his last interview with The Catholic Spirit before he retired, he was asked if he had a parting message.

“Love the Church. Love the Church. Love the Church,” he said. “And remember that the Church is the presence of Jesus Christ in our world.”

Father Lachowitzer recalled Archbishop Flynn as “sharp-witted, big-hearted and a devoted disciple of Jesus Christ.

“It was one of his special gifts to be in a parish and leave everyone feeling affirmed and appreciated,” he said. “I remember the first time I heard him open the penitential rite with an invitation to the people to close their eyes and imagine how much God loved them and how pleased God was with them. He invited the people to imagine God smiling upon them. People cried.”

In settings large or small, Archbishop Flynn was at home sharing stories with his profound insight into peoples’ lives, often with his self-effacing sense of humor and an Irish twinkle in his eyes.

Father John Ubel, rector of the Cathedral of St. Paul, called Archbishop Flynn “the most human man I have ever known.”

“Archbishop Flynn could read you like a book because he took the time to become familiar with the pages,” Father Ubel said. “He got to know us as priests, but first as people. We were men who came from families, who lived with parents and siblings, and who bore all the marks of those familial relationships. He will be truly missed, but often remembered with a smile and a story.”

Maria Wiering, editor-in-chief of The Catholic Spirit, contributed to this report

Look for expanded coverage of Archbishop Flynn’s legacy on TheCatholicSpirit.com in the coming days.

Related:

Photos by Dave Hrbacek / The Catholic Spirit

Click any photo for slideshow

Related: