On March 17, 1873, the Irish of Minneapolis and surrounding areas gathered for Mass, filling the largest church in the city to overflowing. After hearing Father James McGolrick preach on the history of Ireland and the place of the Irish people in America, they poured out of Immaculate Conception to begin a St. Patrick’s Day parade through the city.

At the head of the procession were mounted police, the Emerald Brass Band, Irish Rifles, the Father Mathew Total Abstinence Society and the Youth Temperance Army. Temperance in regard to alcohol was a major theme of the celebration.

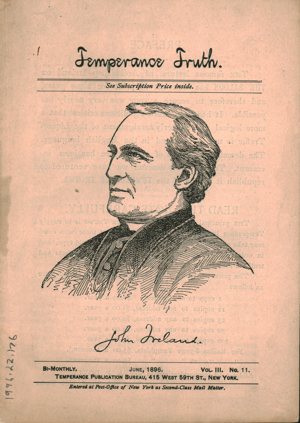

In fact, temperance regarding alcohol was a central aspect of the Irish Catholic community in Minnesota between 1869 and the 1920s. Father (later Archbishop) John Ireland became a leader of the movement when he established the Cathedral of St. Paul’s chapter of the Father Mathew Total Abstinence Society in 1869 with 50 members — and a compelling founding story. As Archbishop Ireland later told it, seven men were gathered in a saloon in downtown St. Paul on a Friday evening when they realized they were on a dangerous path. “Let us go and see Father Ireland and organize a temperance society,” one exclaimed, and they wrote a petition, convinced the saloon keeper to sign it, signed it themselves and stumbled over to Father Ireland’s house with their paper in hand. Without hesitation, Father Ireland agreed to champion a temperance society. He was continuing a tradition of support from Catholic bishops in Minnesota for total abstinence from a substance that was known to ravage frontier communities.

Named for a Franciscan friar who led a temperance crusade in Ireland, the Father Mathew Total Abstinence Society called members to take a pledge against all alcohol consumption. Before immigrating to the United States, Ireland had served Mass for Father Theobald Mathew. He recalled taking Father Mathew’s pledge for the first time at age 6, and that Father Mathew sometimes referred to him as “his little teetotaler.” As a leader in the Catholic Church in Minnesota, he advocated tirelessly for abstinence among priests and parishioners, becoming known as the “Father Mathew of the Northwest.” By 1873, Father Ireland boasted that more than 25 parishes in Minnesota had independently organized temperance societies. He advocated for one at every English-speaking parish in his archdiocese. Members had to be a minimum of 12 years old, and after 1876, Archbishop Ireland, who became a bishop in 1875, welcomed women in addition to men.

Temperance societies became central fixtures in the community. Archbishop Ireland liked to remind pastors that their parish temperance society was in competition with the local saloon, which drew in customers with free lunches and social activities. In response, parishes began to offer meals, social activities, libraries and public education. Dues-paying members of the Father Mathew Society of St. Paul could also expect the society to provide them with an income while they were ill and to defray their funeral expenses. Churches became the communal gathering place, rather than the pub.

For Archbishop Ireland, this mission was part of a larger project of transforming Irish Catholic refugees into respectable middle-class Americans. Even after Father Ireland became archbishop, he continued to support the temperance movement. He spoke at the national total abstinence convention. When he established Minnesota farm towns to resettle Irish refugees, he insisted they be dry. Archbishop Ireland believed abstaining from alcohol would make the Irish better Catholics and better Americans. German Catholics disagreed. They continued to drink their beer, supporting the booming brewing business in St. Paul.

Luiken is a historian with a Ph.D. from the University of Minnesota and a lifelong Catholic in the Archdiocese of St. Paul and Minneapolis.