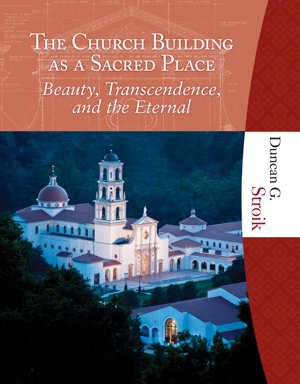

“The Church Building as a Sacred Place: Beauty, Transcendence and the Eternal” by Duncan G. Stroik. Liturgy Training Publications (Chicago, 2012). 175 pp. $75.

A new book by University of Notre Dame architecture professor Duncan G. Stroik has so many exquisite photos of churches that one might think at first glance it is another beautiful coffee-table book. But “The Church Building as a Sacred Place: Beauty, Transcendence and the Eternal” is so much more than pretty pictures.

Stroik writes in clear prose what every Catholic should know about the way a church building’s exterior and interior should reflect and enable the sacred actions that are celebrated within its walls. Helping to illustrate and enforce these concepts are more than 170 photographs and drawings that date from early Christian places of worship to churches built in the 21st century.

In his introduction, Stroik argues that the book is not a history of architecture. Nevertheless, the average person will learn a great deal about the architectural history of the Catholic Church in virtually every one of the 23 chapters in the book. Those chapters are divided into four parts: Principles of Church Design; Church Architecture Today; Modernism and Modernity; and Renaissance and Renewal.

Throughout the book, Stroik — who considers ecclesial architecture a “noble ministry” — displays a firm grounding in theology and philosophy as he explains the principles of Catholic architecture. He alludes frequently to various church documents such as the Catechism of the Catholic Church, the Second Vatican Council’s Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy (“Sacrosanctum Concilium”) and the General Instruction of the Roman Missal.

As a practicing architect who has designed several significant new churches and extensive renovations himself, Stroik also offers concrete solutions for renovating or building churches that will evoke a sense of the sacred and be will be fitting symbols of the God’s house for generations to come.

Many of the chapters in the book were written as essays by Stroik over the past 18 years and published in journals, while some were composed for this book. Thus, the chapters do not necessarily build upon each other, but each treats its subject matter in a complete manner that allows the reader to understand the chapter’s topic independently from the other chapters.

A fascinating appendix in the back of the book on “The Sizes of Churches” allows the reader to compare the size and scale of many famous Catholic churches in Europe to some prominent churches in the United States.

One does not have to read far into the book to learn that Stroik dislikes churches designed by modernist architects over the past century that look like modern secular buildings and are configured like theaters or auditoriums with minimal iconography. However it is not just his personal dislike, but rather a strong sense that such churches give no visible indication of the sacredness of the building or the celebration that occurs therein, and they do not serve the needs of Catholic liturgy. (Indeed, this reader was struck by one photograph of the interior of a modernist church that looked very much like a prison with its plain concrete walls.)

“We need an architecture that helps raise our hearts and minds to heaven,” he writes, and he proves his case throughout the book by citing official Catholic Church documents.

In his section on modernism, Stroik contends that many modernist architects were influenced by Protestant meeting-room-style churches as well as a desire to conform ecclesial design to the latest secular buildings. The result, he writes, are functional-looking buildings that do not function well for Catholic worship.

He builds a strong case for his assertion that classical and medieval churches are still relevant to contemporary culture, for they are a timeless “catechism in paint, mosaic and stone” that appeals in any age. Indeed, he notes that it often was a poorly formed liturgist and not the people in the pews who demanded many of the renovations — some would say “wreckovations” — of Catholic churches after the Vatican II.

Stroik writes that sacred architecture is part of our Catholic patrimony, but he does not advocate simply copying famous Catholic churches of the past. Rather, he believes that church renovators and designers should learn from those classical models and apply to contemporary buildings what they learn about making a church beautiful and evocative of the sacred. To prove his case, he presents photos of several Catholic churches built in the last few years that are innovative and modern while at the same time beautiful examples of ecclesial architecture.

“As architects and artists regain the balance between tradition and innovation, architecture will become a humanistic enterprise once again,” Stroik writes.

Stroik’s final chapter contains 20 “prophecies” about the future of Catholic architecture in which he predicts: “A renaissance of Catholic architecture will ensue, when large numbers of the lay faithful and the church leadership begin demanding beauty in the house of God.” Many Catholics probably hope that Stroik is a prophet in his own time.

Carey is a freelance writer based in Indiana.